LOS ANGELES — Just four days before a raging inferno descended on his Pacific Palisades house, Rick Citron and his wife left town to mourn the recent death of their adult daughter.

They never imagined it would be the last time they’d see their home of more than 40 years.

Around 5 p.m. on Jan. 7, Citron remotely turned on his Tesla car camera to watch the unimaginable unfold.

He saw large embers fly through the air, swirling around the home on Ocampo Drive he purchased in 1982. “This doesn’t look good,” he remembers thinking before forcing himself to get some sleep around 11 p.m.

But at 5 a.m. on Jan. 8, a sinking feeling startled him awake. He switched on the camera and saw firefighters running away from his house, pulling a hose behind them, trees lighting up like matchsticks. He switched to the rear-view camera and saw his house ignite. A few moments later, his electric car exploded.

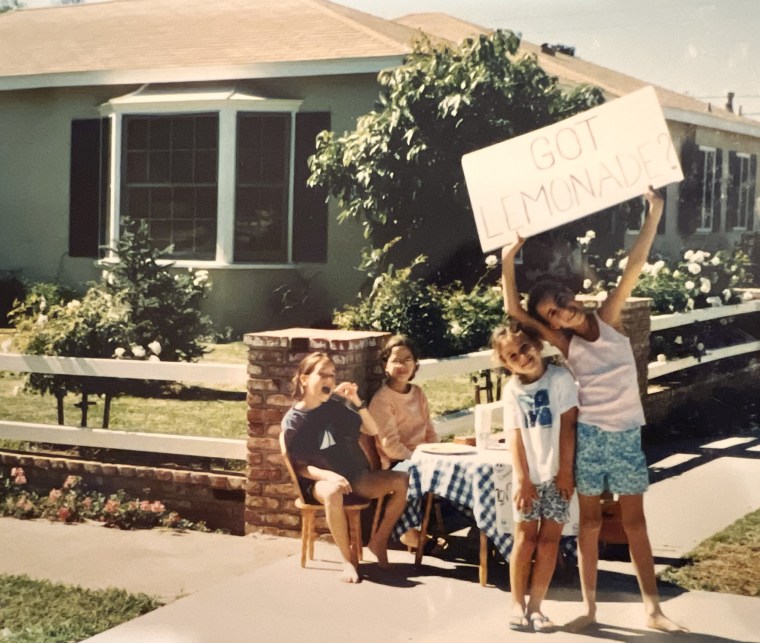

“I just thought to myself, ‘I’ve lost 40 years of history that the family has built,’” he said. “All three of our kids grew up there — learned to ride their bikes there, went to local schools there. I coached my kids’ sports at the park. It was a way of life — the community.”

The siege began on Jan. 7 when a fire fed by hurricane-force winds and dry conditions consumed the oceanside neighborhood. Later that day, another equally fierce fire across Los Angeles County destroyed parts of Altadena. At least 27 people were killed between the two fires that lay waste to densely populated parts of the county.

Citron’s home was one of more than 3,500 structures destroyed in the Palisades Fire, which leveled much of the Pacific Palisades neighborhood and nearby Sunset Mesa.

“He lost his sister and he lost his home,” Sherry Citron, Rick Citron’s daughter-in-law, said about her husband, Justin. “How do you even process that? The house was part of our future.”

Situated atop hills and bluffs overlooking the Pacific Ocean, Pacific Palisades is known as a playground for the rich and famous. But it is also home to families that purchased houses and condos generations ago, when prices were a fraction of what they are today.

For years, there was a small sporting goods store and a popular deli where kids congregated after school, an ice cream store frequented by families and a beloved bookstore that drew locals to its cramped stacks.

It was an L.A. version of Main Street USA that gave the Palisades a small-town feel within a sprawling metropolis. The old village of mom-and-pop shops was torn down years ago by billionaire developer Rick Caruso, who replaced them with high-end brands like Saint Laurent and Lululemon.

“At that time, it was just down to earth,” said Glenn Turner, who has lived in neighboring Sunset Mesa since 1988. His home was destroyed in the fire, but he intends to rebuild using insurance money and savings.

“You had people who worked at Vons who could live there,” he added, referring to the West Coast grocery chain. “You had school teachers who could live there.”

Vestiges of the old Palisades remained even after new development came in. Many longtime residents who purchased their slice of paradise when it was still affordable had planned to pass down their homes to their children and grandchildren, many of whom could never afford to buy in today’s unforgiving market.

“You could live in the Pacific Palisades on basically working-class salaries,” said Wade Graham, a historian and University of Southern California-affiliated scholar. “It was never a place that was dominated by the wealthy until very, very recently.”

Graham described the Pacific Palisades as a series of disparate real estate ventures that grew over time to become one community.

In 1911, a movie producer created a studio called Inceville at the intersection of what is now Sunset Boulevard and Pacific Coast Highway. It was spread over 18,000 acres at its peak and could house 700 crew members. In 1915, a fire nearly burned down the studio, according to Hollywood lore.

The intersection became a chokepoint last week as hundreds of fleeing residents tried to funnel onto PCH from Sunset, one of the only routes out of the neighborhood.

In the 1920s, a Methodist organization chose the Palisades bluffs north of Santa Monica as a prime location to build a church and host its meetings, according to the Pacific Palisades Historical Society. Modest, single-family homes began to spring up in the area, which later became known as the “alphabet streets,” many of which were razed in last week’s firestorm. The area also served as a shelter for Jewish creatives and intellectuals fleeing the horrors of Hitler’s Germany.

“Our parents discovered the Palisades 40 years ago when it was kind of in the middle of nowhere,” said Birdie Bartholomew, whose sister and aunt and uncle lost their homes in the fire. “They built their lives there, which in turn gave us this community. That’s what was lost.”

As neighboring Santa Monica urbanized, the Palisades maintained its attainable allure for decades, Graham said. Further north on PCH, Sunset Mesa became a new Shangri-la.

A planned community built atop a hill overlooking the ocean and the nearby Getty Villa museum, Sunset Mesa started as a set of condos. They were followed by some 500 midcentury homes with starting prices of about $38,000, according to historical records. Now, many of those homes are valued at upward of $3 million.

In 1996, flames licked its western hillside when wildfire ravaged Malibu to the north. Sunset Mesa was spared, but the threat of fire has always loomed in the Santa Monica Mountains.

“The Mesa felt like the safest place on Earth,” said Jason Silver, whose parents moved to the neighborhood in 1988. “You could walk down at the beach, surf in the ocean, and then walk back home when the lampposts were coming back on.”

Separated from the Palisades by rugged terrain and the museum, Sunset Mesa was a community all its own. Every day around 4 p.m., a group of some 16 families and their dogs gathered at the corner of Kingsport Drive and Oceanhill Way to share news of the day. It eventually became known as “doggy corner” and served as a safe haven, especially during the Covid-19 pandemic when people were isolated from loved ones and colleagues.

“We would be outside having martinis 6 feet apart,” said Anne Salenger, who founded “doggy corner” in 1981. Hers was one of just two homes in the group that did not burn down.

Jon Cherkas, who moved to the neighborhood in 2001, said he didn’t start meeting neighbors until his wife began taking their black Labrador for walks. He noticed the people congregating every day just a few blocks from his house and figured he would tag along. Soon, a new community blossomed around him.

After the fire hit, several members of doggy corner met in Century City for lunch. No dogs were present, he said, but it felt like being around family again.

“It was so nice to hug our friends and to see their faces that we haven’t seen forever,” he said. “It’s only been a week or so, but it feels like forever.”

Like most members of the meetup, Cherkas plans to rebuild. Frankly, he can’t imagine living anywhere else.

“I will stay for the rest of my life,” he said. “It will be passed down to my kids.”

Alicia Victoria Lozano is a California-based reporter for NBC News focusing on climate change, wildfires and the changing politics of drug laws.